The two main types of diabetes have undergone several changes in nomenclature over the years: juvenile diabetes became insulin-dependent diabetes which then became type 1 diabetes; adult-onset diabetes became non-insulin dependent diabetes which finally became type 2 diabetes.

There were reasons for these changes (for example, although non-insulin dependent diabetes meant that persons with this type of disease did not depend on insulin therapy in order to continue living [unlike the insulin-dependent patients], it seemed confusing since about one-quarter of the so-called non-insulin dependent patients were indeed injecting themselves with insulin). Thus, the American Diabetes Association changed the names of these conditions over the years to minimize confusion.

We will use T1D to denote type 1 diabetes (the old juvenile type) and T2D as the short form for type 2 diabetes (the old adult-onset type). Persons with T1D are typically diagnosed as children at any age through teenage. They usually present with weight loss, increased thirst and urination, fatigue, glucose (sugar) in the urine, but will sometimes first come to medical attention in the emergency room in a semi-comatose or comatose state with a metabolic disorder secondary to the T1D known as diabetic ketoacidosis. Children under the age of two years are more likely to first be seen with this serious condition. Because individuals with T1D have no insulin at all, their blood sugars are sky-high when they are diagnosed.

Insulin, the master metabolic hormone that does much more than merely control blood sugar, is produced in special cells located within the pancreas known as beta cells. In T1D, these beta cells are destroyed by an autoimmune process, likely the result of a genetic susceptibility coupled with exposure to a specific viral infection or some other trigger (researchers have yet to identify the viruses or other infectious agents responsible for setting off the immune cascade). Without insulin, the T1D patients are unable use their blood sugar for energy, and need to switch over to burning fat for this essential process; as a byproduct of this fat-burning, they produce chemicals called ketones which can eventually lead to the ketoacidosis mentioned above.

In T2D, there is no autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing beta cells; the T2D patients usually have normal or even elevated levels of circulating insulin, so absence of beta cells is not the problem. So, why do they get diabetes?

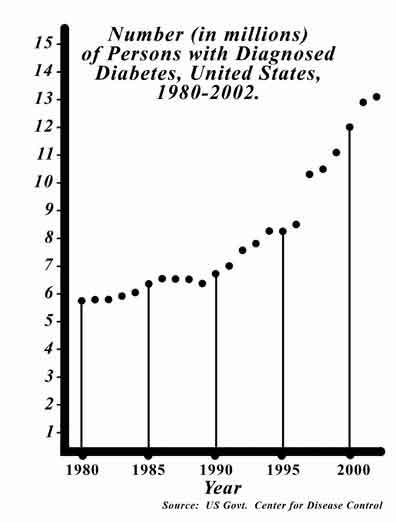

Most of these T2D individuals have what is labeled as insulin resistance. This is a condition where the cellular targets of insulin action (mainly the liver and muscle cells) require more insulin than is circulating to get the job done. This cellular resistance to insulin action signals the body that it needs more insulin in circulation, thus calling on beta cells to make more. Increased insulin resistance can arise in different ways, for example, certain medical conditions (e.g., testosterone deficiency) and certain drug therapies (for instance, some HIV/AIDS drugs) can cause it, but by far, the most common reason is obesity and associated physical under activity. And this is precisely why we now have an epidemic of T2D.

But wait just a minute, you might say: I know plenty of obese, sedentary people who do not have diabetes—what about them? And further, I know some non-obese adults who became diabetic later in life—what about them? The answers to both of these questions lies in genetic diversity. For the obese non-diabetic, it seems that these people are able to keep up with the increased demand that their bodies make on their beta cells for more insulin, while the obese diabetic cannot keep up, so they have a relative insulin deficiency even though they are still able to produce it.

The non-obese T2D patient appears to have a genetic predisposition towards either increased insulin resistance or (more likely) a defect in the ability of the beta cell in secreting insulin.

Well then, how do we prevent diabetes? For T1D, we do not know. Since it was known to be an immune-based condition, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded a large, expensive study which gave small amounts of oral or injected insulin to high-risk relatives of patients with T1D hoping to produce blocking antibodies and “immunize” them against T1D. These tactics failed.

Prevention of T1D is likely 5-10 years away, using information based on either genetic, immunologic or infectious disease findings. For T2D, it is a different story. One needs only maintain proper weight and exercise for just 20 minutes three times per week for the vast majority of Americans who are at risk for T2D. That’s it.

Now please read The Gay Caveman Diet I and II in order to prevent diabetes…

© Copyright 2009 Doctor's Weekly Commentary

May not be reproduced whole or in part without citation and/or link to this site

No comments:

Post a Comment